There’s a man in my cooking class who makes the rest of us look unserious.

He’s a retired insurance executive from New Orleans. Before the three-month program even started, he’d already completed two internships—one at a Michelin-starred restaurant. When this course ends, he’ll head straight into another year-long apprenticeship. His goal: open a small restaurant back home.

He and his wife (she’s taking a sommelier course) have rented a single room and a kitchen in the same building as the school. Every night after class, while the rest of us wind down, he’s there again—practicing a different dish, adjusting sauces by milligrams, timing every movement.

He’s obsessed.

It reminds me of something David Goggins—the Navy SEAL who famously completed Hell Week three times, once with broken legs—wrote in his memoir Can’t Hurt Me:

“Motivation is crap. Even the best pep talk or self-help hack is nothing but a temporary fix. It won’t rewire your brain. Motivation changes exactly nobody.”

His advice instead:

“Be more than motivated, be more than driven—become literally obsessed to the point where people think you’re nuts.”

People prefer motivation because it sounds reasonable. It doesn’t frighten normies. Obsession sounds unhinged. Excessive. Imbalanced. But that’s precisely why it works.

The difference between the two is the difference between a match and a furnace. Motivation burns hot for a minute. Obsession keeps the fire going when no one’s watching.

From Motivated to Obsessed

I started my cooking journey motivated. I had my reasons. But motivation only got me through the door. If I want to bend the learning curve—to move from pretty good to dangerously competent—I need obsession.

Obsession begins when the class ends. It’s the work no one asked you to do: practicing after hours, reading cookbooks instead of scrolling, watching chefs on YouTube and pausing every few seconds to mimic the flick of their wrist. It’s when curiosity starts to feel like compulsion.

There’s a scene in Roadrunner, the Bourdain documentary, where his Parts Unknown crew complains that Tony wouldn’t shut up about mixed martial arts. In downtime, they couldn’t get him to talk about anything else. Soon enough, nobody wanted to sit next to him. That’s obsession. When you start boring people, you’re probably doing something right.

Here’s a test: are you canceling plans not because you have to, but because you want to? Are you choosing your craft over Netflix, not out of guilt but because the work feels more alive? That’s the line.

Obsession isn’t always spontaneous—you can build the conditions for it. You can make space for it.

When I first arrived in Italy, I was finishing a nonfiction manuscript, taking Italian lessons, and playing tennis every day—on top of cooking school. I was busy but stagnant, spread too thin for anything to take root. So I’ve started pruning. I dropped the extras and let cooking become the main thing.

That’s the first rule of obsession: it needs space and time. You can’t squeeze it in.

The second rule: surround yourself with obsessives. Read, watch, and listen to people who care so deeply it borders on mania. During my screenwriting year, it was Craig Mazin and John August’s Scriptnotes podcast. During surfing, William Finnegan’s Barbarian Days. When I was writing my novel, Stephen King’s On Writing. During my MCAT year, Feynman—scientific obsession distilled into joy.

Obsession feeds on proximity. Spend enough time around people (whether IRL or through outside sources) who care that deeply, and you start to absorb their rhythms.

The third rule: practice on your own. No stopwatch, no deadline, no applause. Cook something no one will taste. Play guitar for yourself. Write a paragraph you’ll delete. Let curiosity drive your reps. That’s where craft becomes instinct.

Finally, have a vision—not a goal, but a scene. We think in stories, not spreadsheets. Goals are sterile. Scenes are alive.

For me, the scene I pictured was Sunday dinners when I got home: friends gathered around a long table, passing bread and wine, laughing. I can see it perfectly—the light through the windows, the smell of garlic and olive oil, someone pouring more wine while the conversation hums. It’s a little like the lunch scene in Before Midnight—people talking over each other, happy, human, unoptimized.

When writing my latest book, the scene was a reading at Shakespeare & Company in Paris (Before Sunset). When I was surfing, it was catching a barrel on my 40th birthday at Kelly Slater’s wave pool. Maybe you’re learning guitar and picture yourself playing a song for your future partner. Don’t stop at the idea—what song? What are you wearing? Who’s there?

Scenes drive you in a way metrics never can. They remind you why the struggle matters—why it’s worth showing up before dawn. That’s how obsession takes root: not from personal KPIs, but from a vision so vivid you can almost live inside it.

The Pattern

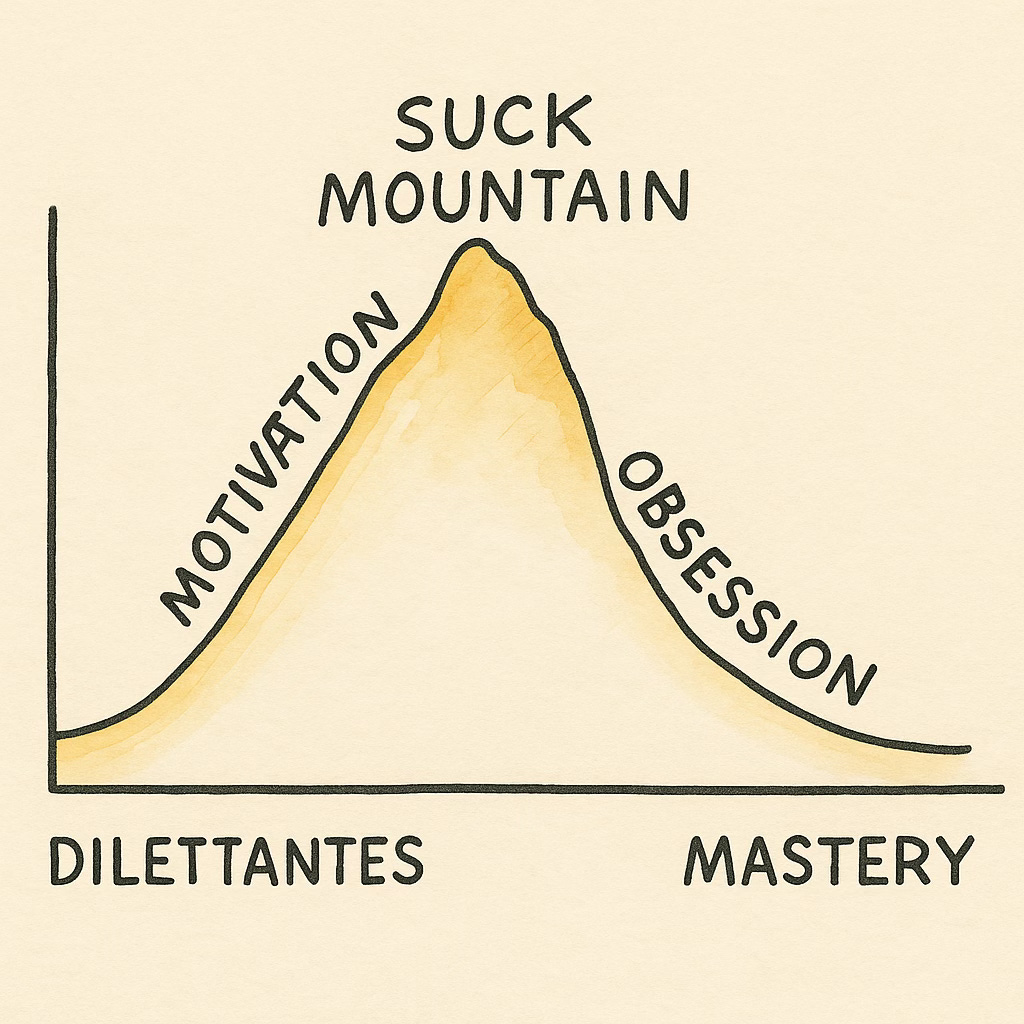

Every one of my new pursuits follows the same curve.

The Honeymoon: a burst of motivation. Everything’s novel, the wins come fast. The first few weeks of surfing when you finally stand up. The early rush of drafting a novel. The thrill of a new PR at the gym.

The Difficult Middle: then comes the stall—the long, uneven stretch where you get knocked on your ass and progress flattens. This is the graveyard of good intentions.

But if you push through that middle, something shifts. Obsession is built on the other side of that slog. It’s what happens when you keep going long enough for your brain to change.

There’s science to explain this. Buried deep inside your brain is a small but powerful region called the anterior mid-cingulate cortex, or aMCC. It doesn’t get much press, but it might be the part of your brain most responsible for what we call grit. It’s the control room for effort—the system that lights up when you do something you don’t want to do, and the one that keeps you from quitting when the novelty wears off.

A 2019 study in Cortex found that people who maintain sharp, youthful minds into old age—“superagers,” they’re called—tend to have stronger, more active aMCCs. This region helps us “persist through difficulty” by evaluating whether the work is still worth the reward.

The aMCC is trainable—but only one way: by leaning into discomfort.

Andrew Huberman describes it this way:

“Your aMCC is a key hub for leaning into undesired effort. It is activated by engaging in behaviors you don’t want to do.”

Read that again: you don’t want to do.

That’s the bridge between motivation and obsession. Motivation gets you started. Doing the thing you don’t want to do—again and again—is what strengthens the aMCC until the dread fades. The task that once felt punishing begins to feel good.

This is what most people misunderstand about mastery: the joy doesn’t come at the beginning. It’s earned later, on the far side of monotony. You cook through enough burnt sauces, study through enough foggy nights, miss enough forehands—and somewhere in that repetition, something rewires. The pain starts to feel productive. The struggle starts to feel good.

And then one day, you catch yourself looking forward to the thing you used to avoid. You’ve gone from motivated to obsessed—not because of a pep talk, but because you’ve literally changed your brain.

You can’t hack this process. You can’t gamify your way past it. You just have to do the hard thing, again and again, until it begins to feel different.

Embrace the Friction

If there’s a secret to mastery, it’s not the grand gesture—it’s the repetition.

But repetition doesn’t always look calm. Sometimes it’s the manic all-nighter, the solitary Tuesday, the quiet refusal to stop. Obsession has a pulse—it speeds up, slows down, sometimes takes over. What matters is that you keep showing up, however messy it looks from the outside.

One more dish. One more page. One more drill.

Over time, the friction turns into fuel. What once felt like punishment starts to feel like peace.

And if you stay with it long enough, there’s a moment when you realize you’ve crossed the line. You’re no longer the person doing the thing—you’re the person who does.

As they say, the dancer has become the dance.

That’s the reward. Not applause or achievement. Just the quiet satisfaction of becoming inseparable from the thing you now love—even if it drives you a little mad.